GEW Intelligence Unit

Research Supervisor and Editor: Dr. Hichem Karoui

I. Executive Summary

This report examines the multifaceted arguments supporting the premise that Iran will not be decisively defeated in a conflict with Israel, even with direct U.S. military involvement. Iran’s strategic depth is rooted in its adaptive military doctrine, extensive hardened infrastructure, a resilient “resistance economy,” and a regime capable of maintaining internal cohesion amidst external pressure. These factors, combined with the inherent challenges and significant geopolitical costs for the United States and Israel in a protracted asymmetric conflict, suggest that a conclusive military victory against Iran is highly improbable.

Key observations indicate Iran’s hybrid warfare approach, combining asymmetric tactics with modern conventional capabilities, enables it to impose costs and sustain conflict despite technological disparities. Deeply buried and dispersed nuclear and military facilities are exceptionally difficult to neutralize, even with the most advanced U.S. munitions, ensuring strategic survivability. A sophisticated sanctions evasion network and a focus on non-oil exports provide Iran with a degree of economic resilience to endure prolonged pressure. The Iranian regime demonstrates robust internal control, capable of leveraging external threats to foster national unity and suppress dissent, mitigating the risk of internal collapse. Historical precedents from asymmetric conflicts highlight the immense difficulty for superior conventional forces to achieve decisive political outcomes against determined, adaptable adversaries. Finally, direct U.S. intervention carries substantial risks, including regional destabilization, economic disruption, and the potential for a protracted engagement without guaranteeing strategic objectives.

II. Introduction

The escalating tensions and recent direct military exchanges between Israel and Iran have intensified global focus on the potential for a wider regional conflict. A critical question arises: what would be the outcome if the United States were to directly join Israel in such a confrontation? This report addresses the specific premise that Iran would not be decisively defeated, even under this exacerbated scenario.

Iran’s adaptive military doctrine, characterized by a sophisticated hybrid approach and extensive proxy networks, coupled with its deeply embedded and hardened defensive infrastructure, a resilient “resistance economy” designed to circumvent sanctions, and a regime demonstrating robust internal cohesion, collectively present formidable obstacles to a decisive military defeat, even if the United States were to fully intervene. Furthermore, the significant strategic, economic, and geopolitical costs associated with such an intervention for the U.S. and Israel render a conclusive victory elusive, pushing the conflict towards protracted engagement rather than decisive resolution.

III. Iran’s Strategic Military Doctrine and Capabilities

A. Asymmetric Warfare and the “Axis of Resistance”

Iran’s military doctrine, largely shaped in the 1980s, emphasizes asymmetric methods of warfare, including supporting proxy militias in the region to confront militarily superior foes and project influence.1 This approach was forged in the context of conflicts like the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) and the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), where Iran identified the potential to export the ideology of the Islamic Revolution through unconventional means.1 The Quds Force, a paramilitary element of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), is central to these operations, leading or conducting many of them and exercising control over key proxy groups such as Lebanese Hezbollah and Kata’ib Hezbollah in Iraq.2 This distributed network allows Iran considerable influence across Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, and western Afghanistan, effectively reducing Iran’s official footprint while maintaining significant strategic reach.2

Iran’s asymmetric warfare is understood as a holistic strategy designed to overcome its inability to match U.S. conventional power and resources by exploiting perceived Western vulnerabilities.2 This paradigm is often described as “hybrid warfare,” combining attributable but deniable operations, proxies, and technologies to destabilize targets and achieve objectives short of outright war.2 These “fait accompli” campaigns are intended to achieve military and political objectives rapidly, creating irreversible facts on the ground before an adversary can respond, thereby reducing or denying adversary response options.2

While the “Axis of Resistance” has recently experienced “withering setbacks” and “major defeats,” with Hezbollah’s capabilities severely degraded by Israeli actions 3 and the fall of the Assad regime impacting supply routes 3, these groups retain significant disruptive potential. Hezbollah, despite being weakened and facing internal resentment within Lebanon, is still believed to possess an arsenal, including ballistic missiles, and may intervene if the conflict escalates into a full-scale war.5 The Houthis in Yemen, despite U.S. military intervention degrading their positions, have demonstrated pragmatism and the ability to reconstitute capabilities, distinguishing themselves with missile strikes on Israeli territory.8 Similarly, Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) groups remain infiltrated by Iran, enabling Tehran to pursue its objectives in Iraq while obfuscating its direct involvement.10

The data suggests that while Iran’s proxy network has faced significant challenges, its strategic value for Iran’s asymmetric approach persists. The “Axis of Resistance” is adapting by “turning back to basics: local power” and re-engaging in “spoiler tactics and asymmetrical warfare”.4 This is not a sign of defeat but rather a strategic adaptation to maintain influence and impose costs. Even if weakened, these proxies can still generate instability, preventing a decisive victory by forcing adversaries into prolonged, localized engagements. Their continued existence, even in a degraded state, prevents Israel and the U.S. from fully disengaging or declaring a complete victory, shifting the focus from large-scale regional projection to localized attrition and leveraging the internal challenges of target states.

B. Conventional and Hybrid Warfare Evolution

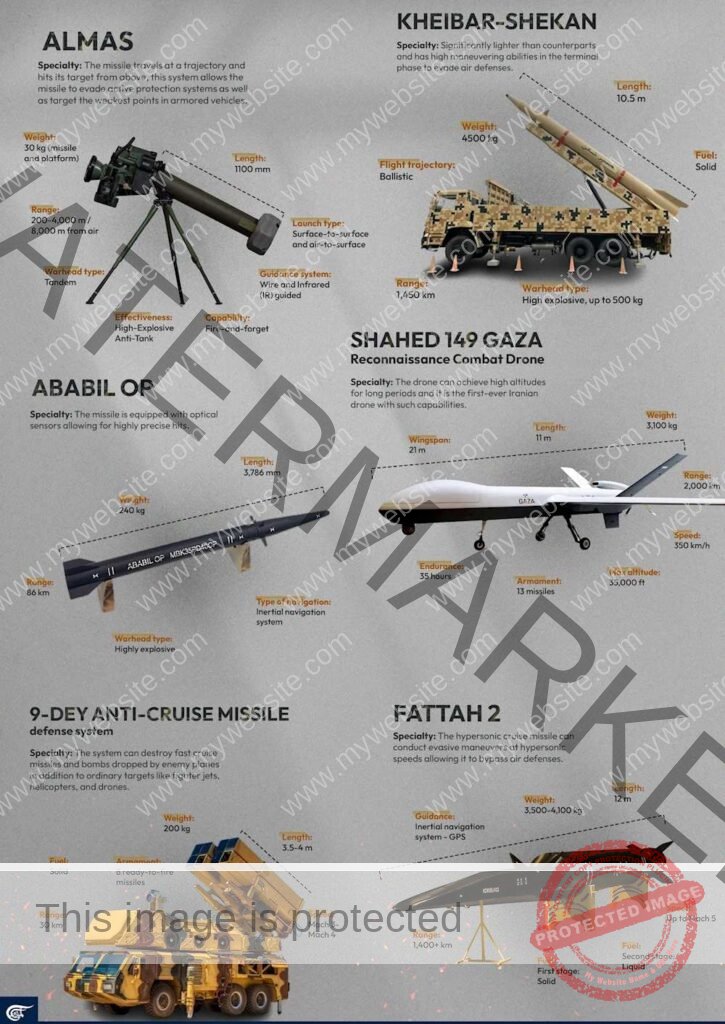

The emergence of a low-cost, modernized native military industry has allowed the Islamic Republic to reinforce its conventional fighting forces and methods, supplementing its unconventional doctrine.1 This modernization encompasses significant advancements in projectile, drone, cybernetic, navy, and land warfare, likely supported by limited technology sharing from Russia and China.1

Iran maintains the largest ballistic missile program in the region, a critical component of its military strategy.2 It also possesses a relatively advanced and capable drone program, exemplified by the Shahed attack drones it has sold to Russia.2 The new ‘Qadr-380’ cruise missile, for instance, can hit targets at a range of 1000 km, utilizing artificial intelligence to adjust routes and flight paths after launch.1 Furthermore, Iran plans to expand its naval operational range by converting a ‘C110-4’ cargo ship into a low-cost swarming drone carrier by 2025.1 Iran’s recent retaliatory strikes against Israel involved approximately 370 ballistic missiles and over 100 drones, launched in multiple waves.13

Iran’s use of waves of Shahed drones followed by ballistic missiles showcases a cost-effective tactic designed to probe and exhaust Israel’s sophisticated missile-defense shield.15 This “saturation strategy” demonstrates that with limited technology, a country can upset an advanced defensive system by emphasizing volume and timing over accuracy.15 This approach lowers the political and economic access cost to war, increasing the urge to strike.15

Israel’s air defense systems, such as the Iron Dome and other advanced systems, are highly effective but come at a significant cost, with a single Iron Dome interception costing approximately $50,000 and other systems running over $2 million per missile.14 In contrast, Iranian drones and missiles are described as “low-cost”.1 If Iran can continue to produce and launch these cheaper munitions, even at a limited rate (estimated at 50 missiles per month before the current campaign) 16, and Israel and the U.S. must intercept them with much more expensive systems, this creates an unsustainable economic burden for the superior power over time. This dynamic suggests that Iran’s goal is not necessarily battlefield dominance but “survivability, denial, and long-term attrition”.15 By continuously forcing Israel and the U.S. to expend high-value interceptors on low-cost threats, Iran can drain resources and political will, preventing a decisive victory and instead creating a prolonged, costly engagement.

C. Defensive Posture and Hardened Infrastructure

Iran’s nuclear system is built not just to resist physical strikes but to survive them strategically, legally, and doctrinally.17 Fordow, Iran’s most fortified enrichment site, exemplifies this, sitting buried 80 to 90 meters deep inside the Kuh-e Daryacheh mountains.17 It is protected by an estimated 260 feet (80 meters) of rock and soil and reportedly by Iranian and Russian surface-to-air missile systems.18 Although Israel has targeted other Iranian nuclear sites like Natanz, causing localized contamination 18, Iran has been building new, deeper cascade chambers at Natanz, modeled after Fordow’s hardened design.17

The IRGC’s Passive Defense Organization has guided this shift since the early 2010s, focusing on hardening and camouflaging sites, moving assets underground, and routing logistics through civilian infrastructure.17 This approach mirrors Soviet and North Korean doctrine, aiming to survive the first strike and reconstitute capabilities afterward.17 Dual-use facilities, buried nodes, and mobile corridors form a system designed not to prevent attack, but to absorb it.17 Iran’s nuclear knowledge is also archived, teachable, and distributed through classified academic programs and military-run technical institutes, ensuring that continuity does not depend on who is killed but on what survives.17

The U.S. is the only country with conventional ordnance, specifically the GBU-57 A/B Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP), capable of penetrating Fordow’s depths.18 Even with this advanced munition, success is “far from trivial” 21, and the exact details of Fordow remain somewhat mysterious, with the possibility of additional facilities up to half a mile underground.19 Israeli munitions, such as the GBU-28 and BLU-109, cannot reach Fordow’s depth, only being capable of targeting above-ground entrances or lightly buried ventilation systems.19 A truly effective dismantlement of Iran’s nuclear program would resemble a ground incursion, involving seizing facilities, securing uranium stockpiles, capturing schematics, and debriefing or removing scientists.17 Without such an extensive ground operation, airstrikes alone offer the “appearance of resolution, not its substance”.17

Iran’s defense strategy is explicitly about surviving the first strike and reconstituting afterward.17 This is coupled with the extreme difficulty of destroying deeply buried facilities 17 and the distributed nature of its nuclear knowledge.17 Even if initial strikes cause damage, the system is designed for recovery. This inherent survivability means that even if attacked, Iran can continue its program, preventing a “defeat” in the sense of complete dismantlement. This allows Iran to maintain “latency”—the ability to weaponize rapidly without openly violating the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)—thereby maximizing its leverage while minimizing legal risk.17

Table 1: Iran’s Key Military Capabilities and Defensive Strengths

| Category | Key Features/Capabilities | Relevant Snippet IDs |

| Military Doctrine | Asymmetric warfare, hybrid warfare, complementing unconventional doctrine with conventional capabilities, “fait accompli” campaigns, strategic transformation in response to challenges. | 1 |

| Proxy Networks | Quds Force control over groups like Lebanese Hezbollah, Houthis, Iraqi PMF; distributed network for regional influence; turning to local power and spoiler tactics amidst setbacks. | 2 |

| Missile Arsenal | Largest ballistic missile program in the region (~2,000-3,000 missiles est.); ‘Qadr-380’ cruise missile with AI for route adjustments; production capacity of ~50 missiles/month. | 1 |

| Drone Capabilities | Relatively advanced and capable drone program (e.g., Shahed drones); low-cost swarming drone carriers (converted cargo ships); saturation tactics to exhaust air defenses. | 1 |

| Cyber Warfare | Growing cyber warfare capability; sophisticated information operations capability. | 2 |

| Naval Capabilities | IRGC Navy focused on Persian Gulf/Strait of Hormuz; expansion of operational range at sea with drone carriers. | 1 |

| Hardened/Dispersed Infrastructure | Fordow buried 80-90m deep in mountains; Natanz building deeper chambers; Passive Defense Organization guides hardening, camouflaging, underground assets; dual-use facilities. | 17 |

| Internal Security Forces | IRGC as ideological praetorian guard; decentralized command-and-control with provincial units; dual mission of countering external and internal threats (suppressing social unrest). | 33 |

IV. Economic Resilience and Sanctions Circumvention

A. The “Resistance Economy” Doctrine

Iran has strategically responded to sustained external pressure by promoting its “resistance economy,” a doctrine emphasizing domestic production, services, and technology.24 This approach aims to reduce the country’s reliance on volatile oil markets and cushion the impact of international sanctions.24 The doctrine’s origins can be traced to the painful lessons of the Iran-Iraq War, which highlighted the dangers of relying solely on border defense, and the subsequent recognition that national survival necessitated projecting power beyond its frontiers due to a lack of natural defensive boundaries and dependable strategic allies.26 The Islamic Republic institutionalized and ideologically redefined this “forward defense” posture, particularly after the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, perceiving both a strategic imperative and an opportunity to expand its influence.26

As part of these diversification efforts, the service sector has emerged as a key contributor to Iran’s GDP.24 Furthermore, there has been significant growth in non-oil exports, signaling a strategic shift away from oil dependency.27 Iran is actively working to bolster its economic resilience through infrastructure initiatives, such as expanding its Special Economic Zones (SEZs), and by leveraging international transport corridors like the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC).24 These measures are part of a broader strategy to decrease vulnerability to external economic pressures.

The “resistance economy” is not merely a reactive measure but a “structural pillar” of Iran’s regional strategy and a “deliberate design” to insulate the regime from external shocks and internal dissent.26 While Iran’s economy is indeed facing a “severe downturn” with “deep cracks” 24 and may struggle to “last long” in a drawn-out conventional war 29, the fundamental objective of this economic strategy is endurance rather than prosperity. The ability to “absorb” and “outlast” pressure is central to the regime’s survival doctrine.23 This implies that even if economically battered, Iran’s “resistance economy” and its methods of circumvention are designed to prevent total collapse and enable the regime to continue funding its military and security apparatus.28 Therefore, economic pressure, even with intensified U.S. sanctions, may not lead to a decisive defeat but rather a prolonged, low-level economic struggle that Iran is prepared to endure, preventing a quick capitulation.

B. Sophisticated Sanctions Evasion Mechanisms

To counter American-led sanctions, Iran operates a complex and extensive network designed to circumvent restrictions on its oil exports, primarily to China.30 This network includes intermediaries, front companies, and a “shadow fleet” of tankers.30 The Revolutionary Guards are reported to control up to half of all Iranian oil exports through these illicit networks, which provide financial insulation even during broader economic crises.28

Iranian actors also utilize “shadow banking” networks, involving third-party exchange houses and trading companies in jurisdictions like Hong Kong and the UAE, to conduct international transactions without repatriating funds through official channels.31 These networks are crucial for procuring weapons components and dual-use goods from the international market.31 Common evasion techniques include the use of falsified cargo and vessel documents, disabling or manipulating Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) on vessels, conducting ship-to-ship transfers to mask the origin and ultimate destination of sanctioned cargo, and blending oil from third countries or relabeling it as originating elsewhere (e.g., “Malaysia Crude Oil Blend”).31

Multiple sources discuss the imposition and impact of U.S. sanctions.24 However, evidence suggests that these sanctions have historically failed to achieve their primary goals of preventing destabilization or pressuring Iran into significant policy change.32 Instead, the imposition of sanctions appears to have “expedited the end of Iran’s dependency on US and Western nations for trade and imports,” shifting its economic orientation.32 Furthermore, sanctions have created incentives for Iran to expand its economic and military ties with China and Russia, with Russia reportedly assisting Iran in sanctions evasion.25 If sanctions, even those under a “maximum pressure” strategy 24, have consistently failed to compel policy change or cripple Iran’s ability to fund its strategic objectives, then their role in forcing a “defeat” in a direct war scenario is limited. Iran has developed robust evasion mechanisms, indicating that economic pressure alone will not be sufficient to force a surrender or collapse, especially during wartime when national unity might be heightened.

C. Non-Oil Sector Growth and Strategic Trade Routes

Iran’s non-oil export sector is experiencing significant growth, reflecting a strategic shift in the country’s economy away from oil dependency.27 Non-oil exports surged by 23%, reaching over $25.5 billion in a recent five-month period, with total foreign trade exceeding $103.8 billion in ten months.27 The primary export commodities in this sector include natural gas, liquefied propane, and methanol.27 China remains the largest market for Iranian non-oil products, accounting for $12.3 billion, followed by Iraq and the UAE.27

This growth is part of a broader strategy to diversify the economy and enhance trade relationships, particularly with key partners like China and Iraq.27 Iran is actively leveraging international transport corridors, such as the INSTC, and expanding its Special Economic Zones (SEZs) as part of a broader strategy to bolster economic resilience and reduce reliance on volatile oil markets.24 Russia, a geopolitical partner, has also reportedly sought to assist Iran with sanctions evasion, further supporting these diversified economic pathways.25

While Iran’s economy is highly vulnerable, particularly its oil and gas sector which has fallen far behind global standards due to sanctions and foreign divestment 29, the significant growth in non-oil exports and deliberate efforts to diversify income streams indicate a strategic move to build resilience.24 This diversification, coupled with illicit trade networks, means that even if oil exports are severely disrupted, Iran possesses other, albeit smaller, revenue streams. This economic diversification, while not leading to prosperity, prevents a total economic collapse that might otherwise precipitate a decisive defeat. It allows the regime to maintain a baseline level of funding for its essential operations and security forces, enabling it to “sustain pressure without fracturing”.13

Table 2: Economic Resilience Indicators and Sanctions Evasion Strategies

| Category | Key Figures/Characteristics | Relevant Snippet IDs |

| Economic Vulnerabilities | Iran’s total economy: $340 billion vs. Israel’s $500 billion; 27% of Iranians living on < $2/day; youth unemployment > 20%; chronic inflation (32% in Jan 2025); outdated oil/gas sector; talent drain (1M+ university grads left). | 24 |

| “Resistance Economy” Pillars | Emphasis on domestic production, services, technology; service sector as key GDP contributor; non-oil exports surged 23% ($25.5B in 5 months); overall trade surplus of $28B. | 24 |

| Sanctions Evasion Methods | Complex networks of intermediaries, front companies, “shadow fleet” tankers; IRGC controls ~50% of oil exports; “shadow banking” networks (Hong Kong, UAE); falsified documents, AIS manipulation, ship-to-ship transfers, oil relabeling (“Malaysian Blend”). | 24 |

| Strategic Economic Partnerships | China is largest market for non-oil products ($12.3B); oil exports to China rebounded to 1.74M barrels/day (Feb); leveraging INSTC; Russia assists with sanctions evasion and offers economic partnerships. | 24 |

V. Internal Cohesion and Societal Endurance

A. Regime Control and Security Apparatus

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) plays a central and deeply ingrained role in maintaining the clergy’s control over the nascent regime, having been established as a parallel military to the Artesh shortly after the 1979 revolution.33 Over the decades, the IRGC has metastasized into one of the most dominant political, security, economic, and ideological actors in Iran.33 It is the primary body responsible for controlling Iran’s missile and drone arsenals and for managing and supporting the “Axis of Resistance”.33 Economically, the IRGC controls an estimated 50% of Iran’s oil wealth through subsidiary companies and operates vast construction, telecommunications, and export networks worth billions, providing significant financial insulation even during broader economic crises.28

In terms of internal security, the IRGC Ground Forces have decentralized their command structure in recent years, establishing 32 provincial units designed to operate independently in the event of a decapitation strike against the central IRGC leadership.33 This posture reflects the Ground Forces’ dual mission of countering external threats through guerrilla campaigns and suppressing social unrest internally.33 The regime maintains “tight control over public life,” actively identifying and severely punishing those it considers “traitors or Israeli agents”.34

While “widespread dissatisfaction” and protests have occurred in Iran, as demonstrated during the 2009 Green Movement, 2019 fuel protests, and 2022 demonstrations 28, the regime’s survival mechanism is fundamentally based on “material incentives to the security and military institutions rather than public support”.28 The IRGC’s economic empires and military salaries are directly tied to oil revenue and sanctions-busting operations.28 This structure suggests that as long as these financial foundations remain largely intact, the loyalty of the security forces is maintained, thereby preventing the institutional fracture necessary for regime collapse.28 External pressure alone, even military strikes, is therefore unlikely to trigger regime collapse if the core security apparatus remains loyal. The regime’s ability to “absorb” pressure and its “long game” strategy 23 are predicated on this internal stability, making a decisive defeat through internal implosion less likely during wartime.

B. National Unity in the Face of External Threat

Historical precedents suggest that external attacks by a foreign nation on home soil can “paradoxically generate support and bolster hardliners” within Iran.35 During the Iran-Iraq War, for instance, despite internal dissent against Khomeini, the “vast majority of Iranians united against the common enemy”.34 This historical pattern indicates that a direct military confrontation, particularly one involving the U.S., could trigger a similar rallying effect, with many Iranians who do not support the Islamic regime nonetheless speaking out against the strikes.34

The Iranian government has deliberately avoided framing the current conflict as one of regime survival. Instead, the dominant narrative emphasizes “sovereignty, resilience and proportionate response,” reinforcing a message of national strength and endurance.13 Practical measures, such as keeping metro stations open 24 hours a day for civilian shelter and ensuring ministries continue functioning under attack, further reinforce this message of state continuity and resilience.13

While external attacks can foster national unity 34, they also exacerbate existing economic hardships, such as energy shortages and disruptions to water supply.37 Israeli strikes targeting symbolic and civilian infrastructure, including hospitals and the headquarters of the state media broadcaster, are seen by Iranian analysts as a “socialization of war”—a deliberate effort to generate public pressure on the regime.13 The regime is “very concerned about internal unrest” and has responded by imposing internet restrictions, arresting journalists and dissidents, and deploying riot police, particularly in Tehran.37 This indicates a delicate balance: while initial strikes might rally some support, prolonged conflict and civilian casualties could strain this unity, potentially leading to increased dissent. However, the regime’s robust control mechanisms, including the IRGC, internet blackouts, and arrests, are designed to counter such pressures. The objective is to “sustain pressure without fracturing” 13, meaning they aim to prevent defeat by managing internal discontent rather than relying on overwhelming public support.

C. The Regime’s “Long Game” Strategy

Iran’s leadership operates with a “long game” strategy, demonstrating strategic patience and a deep understanding that Western governments are often constrained by electoral cycles, political fatigue, and media attention.23 The core logic guiding Iran’s actions is one of “survival,” focused on preserving enough capacity and credibility to deter further Israeli escalation and American intervention.13 This approach involves playing for time, keeping Israel engaged in a war of attrition while deliberately delaying any escalation that might transform the scale of the conflict.13

Every restrained retaliatory act by Iran serves as “strategic messaging that Iran is not defeated, it is not isolated, and it is capable of inflicting pain on the other side”.13 Public defiance in Tehran is consistently matched by renewed activity from its proxy groups in Lebanon, Gaza, Yemen, and Iraq, signaling resolve to its allies.23 This strategy allows Iran to gain a geopolitical buffer and exploit friction between Washington and Moscow, as the more actors involved, the more leverage the regime holds, enabling it to delay any real consequence.23

Iran’s strategic approach is not to achieve a conventional military victory but to outlast its adversaries. By drawing out the conflict and continuously imposing costs, even if limited, Iran aims to erode the political will of the U.S. and Israel, making a “decisive victory” impossible in the long run. This aligns with the historical pattern of asymmetric warfare where the weaker party often seeks to survive and endure beyond the point where the stronger power is willing to continue the engagement.

VI. Challenges and Limitations for Adversaries (US and Israel)

A. Technical and Operational Hurdles for Decisive Military Strikes

Decisively destroying the Iranian nuclear program using military means is widely considered “not possible” by many experts, with even limited strikes presenting significant risks and offering limited effectiveness.20 Fordow, Iran’s deeply buried enrichment facility, is particularly challenging; its depth of 80 to 90 meters requires specialized U.S. munitions, specifically the 30,000-pound GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP), and the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber to deliver it.18 Israel currently lacks both this munition and the necessary bomber.18 Even with the GBU-57, successfully destroying Fordow is “far from trivial” 21, and there remains a risk of failure or incomplete destruction, especially given that the exact details of Fordow’s layout are not fully known, with potential for additional facilities deeper underground.19

The highly dispersed nature and advanced state of Iran’s nuclear program, coupled with extensive latent expertise within its scientific community, further complicate efforts to eliminate it militarily.20 Military strikes could inadvertently push the program further underground, both physically and politically, and potentially risk triggering a rapid breakout to weaponization.17

Iran also possesses an arsenal of short-range air defense missiles 40, and its integrated air defense system is overseen by the Khatam ol Anbia Air Defense Headquarters.33 While Israel has reportedly decimated some air defenses 12, attacking multiple targets across Iran would necessitate numerous attack waves to adequately suppress defenses and ensure the penetrating effects required for deep strikes.20 Even the U.S. Air Force and Navy might struggle to destroy all necessary targets in a single attack while simultaneously suppressing defenses and providing weapon redundancy.20

The goal of military strikes is often to “dismantle” or “eliminate” a program.18 However, available evidence consistently indicates that Iran’s program is designed to “survive” 17 and that strikes would only “strengthen the desire for a credible deterrent” 21, potentially leading to a covert pursuit of nuclear weapons. The challenge extends beyond merely destroying facilities; it encompasses eliminating Iran’s knowledge and intent. Therefore, a military campaign, even with U.S. involvement, is unlikely to achieve the complete and permanent destruction of Iran’s nuclear capabilities. At best, it would result in a temporary setback, potentially accelerating Iran’s resolve to acquire nuclear weapons as a deterrent, thereby failing to achieve a decisive victory in the long term and converting a tactical success into a strategic failure.

B. Risk of Protracted Conflict and Strategic Quagmire

Historical examples of asymmetric conflicts, such as the Vietnam War 42, the Soviet-Afghan War, and the insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan 43, consistently demonstrate the immense difficulty for militarily superior powers to achieve decisive victory against weaker, adaptable adversaries employing unconventional tactics.46 These conflicts often devolve into prolonged engagements focused on attrition, where the weaker party aims to outlast the stronger opponent’s political will.46 Lessons from these conflicts highlight “mission creep” 48, the inability to mobilize local support 44, and the high human and economic costs incurred without clear strategic gains.47

The Iraq War experience, in particular, underscores that regime change necessitates nation-building, and prematurely dismantling old institutions without establishing viable replacements creates a dangerous “vacuum” that invites sectarianism and instability.49 Post-regime-change scenarios are inherently unpredictable and could trigger regional destabilization on a scale even greater than that seen in Iraq, with potentially global ramifications.51

A direct U.S. military intervention in Iran risks falling into a similar “forever war” trap.47 Iran’s asymmetric capabilities and resilience mean that even if its conventional forces are degraded, it can shift to insurgency-like tactics, continuously imposing costs and eroding American and Israeli political will. This dynamic would prevent a decisive end to the conflict, as the engagement would simply continue indefinitely at a lower intensity. This protracted engagement would make a “defeat” for Iran unlikely, as its objective is often to outlast the adversary rather than achieve battlefield dominance.

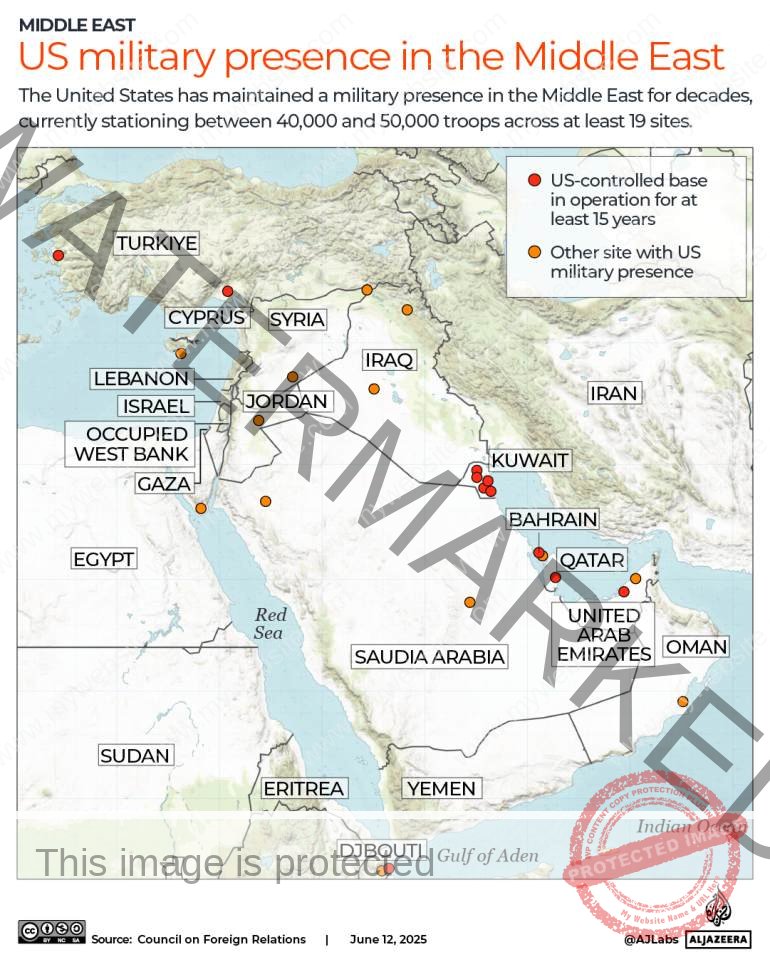

C. Geopolitical and Economic Ramifications for the United States

Direct U.S. military involvement in a conflict with Iran carries substantial geopolitical risks. It could significantly worsen anti-American sentiment across the region, provide potent propaganda for jihadist groups, and potentially lead to violent attacks on U.S. and other Western targets.53 Such intervention also risks triggering immediate nuclear proliferation across the Middle East, compelling states like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Turkey to urgently seek their own nuclear arsenals as a deterrent, thereby irreversibly destabilizing the region.21

Economically, a wider war could severely disrupt or halt the flow of Iran’s oil, a major global producer, leading to significant surges in global energy prices.54 Shipping costs would also rise dramatically due to ongoing disruptions in the Red Sea and the need for rerouting, further impacting global trade.54 Higher energy prices would likely translate into broader inflation, affecting a wide range of consumer goods and potentially forcing central banks to raise interest rates, which could, in turn, stifle economic activity and lead to job cuts.54

From a strategic perspective, U.S. involvement in Iran would divert critical resources and attention from other pressing strategic priorities, such as great power competition with China and Russia.21 It could also foster the perception that U.S. and Israeli interests are perfectly aligned, potentially leading other allies to expect U.S. intervention in their conflicts, even when such involvement runs counter to broader U.S. strategic goals.21

The potential costs of achieving a “decisive victory” against Iran, particularly for the United States, appear to outweigh any perceived benefits. The U.S. would face internal political pressure due to potential casualties 53 and widespread public opposition to “forever wars”.47 This high cost-benefit imbalance acts as a significant deterrent to full-scale intervention, rendering a decisive U.S.-led defeat of Iran strategically undesirable and practically unsustainable.

D. International Constraints and Diplomatic Landscape

The international community has largely called for de-escalation in the Israel-Iran conflict. G7 leaders have issued joint statements urging an end to hostilities while reaffirming that Iran must not acquire nuclear weapons.57 European actors, including Italy, Germany, and the UK, have shown cohesion in pushing for diplomacy, arms control, and a ceasefire, emphasizing the need for renewed diplomatic dialogue with Tehran.53 The UN Security Council has held emergency meetings, with delegates largely agreeing that de-escalation and diplomacy are imperative to avoid further strain in the conflict-ridden region, expressing particular concern over attacks on nuclear facilities.58

Despite deepening their ties with Iran, both Russia and China have maintained cautious diplomacy, offering political support and mediation rather than concrete military action.60 Russia has offered to mediate the conflict and reiterated its earlier offer to store Iranian uranium on Russian soil.61 China, while a key economic lifeline for Tehran through illicit oil purchases, is assessed to have limited capacity to project power on a scale that could tip the balance of power, and is wary of committing resources during heightened tensions in its own region.61 Both nations have urged de-escalation and expressed willingness to play a constructive role in restoring peace and stability.61

While Iran faces a degree of “strategic loneliness” due to a lack of dependable strategic allies 26, it engages in “limited technology cooperation with Russia and China” 1, and these powers provide diplomatic support and economic lifelines.25 The G7 remains divided on a unified response 53, and the UN calls for de-escalation.58 Iran’s strategy involves exploiting friction between Washington and Moscow.23 This international landscape, characterized by multipolarization and a lack of unified resolve for full-scale military intervention against Iran, provides a diplomatic shield. Russia and China’s cautious support, even if not direct military aid, prevents Iran from being completely isolated and provides avenues for sanctions circumvention and limited technological transfer. This international dynamic significantly reduces the likelihood of a globally sanctioned, decisive military campaign against Iran.

Table 3: Challenges for US/Israel Military Intervention

| Category | Key Challenges/Limitations | Relevant Snippet IDs |

| Military/Technical Obstacles | Fordow’s 80-90m depth requires U.S. GBU-57 MOP (Israel lacks); dispersed nuclear program and latent expertise complicate elimination; Iranian air defenses (S-300s, short-range missiles) require multiple attack waves; proxy resilience and ability to reconstitute capabilities. | 5 |

| Strategic Costs | Risk of protracted conflict (“forever war” trap); lessons from Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq on futility of quick victory against asymmetric foes; challenges of nation-building/regime change creating instability; high economic and human costs for intervening powers. | 42 |

| Geopolitical Risks | Increased regional destabilization and anti-American sentiment; potential for attacks on U.S. bases/personnel in the region; risk of triggering nuclear proliferation across the Middle East; strategic distraction from other global priorities. | 21 |

| Economic Ramifications | Significant surge in global oil prices (potentially >$100/barrel); increased shipping costs due to Red Sea disruptions; broader inflationary pressures on consumer goods; potential for central bank interest rate hikes impacting economic growth. | 54 |

| International Constraints | Lack of unified international support for military action (G7 calls for de-escalation, UN urges diplomacy); cautious diplomacy from Russia and China (mediation offers, limited material support); Iran’s ability to exploit friction between major powers. | 1 |

VII. Conclusion

The comprehensive analysis of Iran’s strategic capabilities, economic resilience, and internal dynamics, alongside the significant challenges faced by its adversaries, strongly supports the assertion that a decisive defeat of Iran is highly improbable, even with direct U.S. military intervention. Iran’s hybrid warfare doctrine, characterized by a sophisticated blend of asymmetric tactics and increasingly modernized conventional capabilities, enables it to impose continuous costs and sustain conflict despite technological disparities with its adversaries. Its deeply buried and dispersed strategic assets, particularly its nuclear facilities, are designed for survival and reconstitution, presenting formidable technical and operational hurdles to any attempt at outright elimination through military strikes.

Furthermore, Iran’s “resistance economy,” bolstered by sophisticated sanctions evasion mechanisms and growing non-oil exports, provides a critical degree of economic resilience, allowing the regime to endure prolonged pressure and fund its essential security apparatus. Internally, the regime’s robust control, heavily reliant on the loyal IRGC and its economic interests, coupled with the historical tendency for external threats to foster national unity, mitigates the risk of internal collapse, even amidst societal discontent. The regime’s “long game” strategy, emphasizing endurance and strategic messaging, seeks to outlast the political will of its adversaries rather than achieve conventional battlefield dominance.

For the United States and Israel, the pursuit of a “decisive victory” against Iran risks a protracted, costly engagement with unpredictable and potentially catastrophic regional and global ramifications. Historical precedents from asymmetric conflicts consistently demonstrate the immense difficulty for militarily superior powers to achieve conclusive political outcomes against resilient, adaptable, and ideologically driven adversaries. Direct U.S. military involvement could exacerbate regional destabilization, trigger widespread anti-American sentiment, and potentially accelerate nuclear proliferation across the Middle East. Economically, such a conflict would likely lead to global energy market disruptions and inflationary pressures, while strategically diverting critical U.S. resources and attention from other global priorities. The international landscape, marked by multipolarization and a lack of unified resolve for full-scale military intervention against Iran, further constrains the feasibility of a decisive campaign.

Therefore, future policy considerations should shift from aspirations of decisive defeat to strategies of containment, deterrence, and managing escalation. Recognizing Iran’s enduring capacity to resist and adapt is crucial for developing realistic and sustainable approaches to regional security, acknowledging that a quick, conclusive military solution against such a resilient adversary is unlikely to be achieved.

Works cited

- Iran’s Evolving Military: Complementing Asymmetric Doctrine with Conventional Capabilities, accessed June 19, 2025, https://bisi.org.uk/reports/irans-evolving-military-complementing-asymmetric-doctrine-with-conventional-capabilities

- Asymmetric Warfare Group Iran Quick Reference Guide – Public Intelligence, accessed June 19, 2025, https://publicintelligence.net/awg-iran-quick-reference-guide/

- Why are some key Tehran allies staying out of the Israel-Iran conflict?, accessed June 19, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/iran-hezbollah-iraq-militias-houthis-israel-a257b8e55a96a536710fce91fe022915

- The Axis of Resistance Returns to Its Local Roots – The Century Foundation, accessed June 19, 2025, https://tcf.org/content/report/the-axis-of-resistance-returns-to-its-local-roots/

- Hezbollah watches on as Iran and Israel battle, for now – Al Jazeera, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/6/17/hezbollah-watches-on-as-iran-and-israel-battle-for-now

- Why Hezbollah might sit out the Israel-Iran conflict – Breaking Defense, accessed June 19, 2025, https://breakingdefense.com/2025/06/why-hezbollah-might-sit-out-the-israel-iran-conflict/

- The Fall of Assad’s Regime Shakes Iran’s Proxy Network Across the Middle East, accessed June 19, 2025, https://irregularwarfare.org/articles/assad-fall-iran-irregular-warfare/

- How will Yemen’s Houthis respond to Israel’s war against Iran? – The New Arab, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.newarab.com/analysis/how-will-yemens-houthis-respond-israels-war-against-iran

- Iranian support for the Houthis – Wikipedia, accessed June 19, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iranian_support_for_the_Houthis

- CSAG Strategy Paper: “Iran’s Shadow Army: The PMF’s Growing Influence in Iraq”, accessed June 19, 2025, https://nesa-center.org/csag-strategy-paper-irans-shadow-army-the-pmfs-growing-influence-in-iraq/

- The Leadership and Purpose of Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/leadership-and-purpose-iraq%E2%80%99s-popular-mobilization-forces

- How the militaries of Israel and Iran compare, accessed June 19, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/iran-israel-militaries-mideast-us-613e71aff67f6e1701981583bf699bc6

- How Iran Is Calculating Its War With Israel – Middle East Council on Global Affairs, accessed June 19, 2025, https://mecouncil.org/blog_posts/how-iran-is-calculating-its-war-with-israel/

- The Latest: Israel attacks nuclear program in Iran, drawing waves of missiles, accessed June 19, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/israel-palestinians-iran-war-latest-06-13-2025-baa59e6be9612c12ff2dc2a480830279

- Iran-Israel Conflict 2025: Missiles, Drones, and Military Doctrine Redefining the Battlefield, accessed June 19, 2025, https://stratheia.com/iran-israel-conflict-2025-missiles-drones-and-military-doctrine-redefining-the-battlefield/

- Israel’s attack and the limits of Iran’s missile strategy, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/online-analysis/2025/06/israels-attack-and-the-limits-of-irans-missile-strategy/

- Why Iran’s Nuclear Program Cannot Be Dismantled from the Air – The Cipher Brief, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.thecipherbrief.com/iran-nuclear-airstrikes

- What to know about bunker-buster bombs and Iran’s Fordo nuclear facility, accessed June 19, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/bunker-buster-bomb-israel-iran-fordo-fordow-b2-nuclear-8a612cbf16aa0f99bd9992334ffc93d7

- Options for Targeting Iran’s Fordow Nuclear Facility – CSIS, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/options-targeting-irans-fordow-nuclear-facility

- The Challenges Involved in Military Strikes Against Iran’s Nuclear Programme – RUSI, accessed June 19, 2025, https://my.rusi.org/resource/the-challenges-involved-in-military-strikes-against-irans-nuclear-programme.html

- Restraint Towards Iran Serves US Interests – Stimson Center, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.stimson.org/2025/restraint-with-iran-serves-us-interests/

- The Israeli Raid on Syria That Exposed the Weakness of Hardened Targets, accessed June 19, 2025, https://mosaicmagazine.com/observation/israel-zionism/2025/05/the-israeli-raid-on-syria-that-exposed-the-weakness-of-hardened-targets/

- Iran uses diplomacy to buy it time to continue building nuclear arsenal | The Jerusalem Post, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.jpost.com/opinion/article-857561

- Cracks in Iran’s Resistance Economy Amid Renewed Maximum Pressure, accessed June 19, 2025, https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2025/05/04/cracks-in-irans-resistance-economy-amid-renewed-maximum-pressure/

- U.S. Sanctions on Iran – Congress.gov, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12452

- Iran’s strategic loneliness: From regional overextension to regional embrace? | Clingendael, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.clingendael.org/publication/irans-strategic-loneliness-regional-overextension-regional-embrace

- Head of IRICA Reports 23% Growth in Iran’s Non-Oil Exports, accessed June 19, 2025, https://iranpress.com/content/299998/head-irica-reports-23-growth-iran-non-oil-exports

- Real-Time Analysis: Iran After the Israeli Strikes: Regime Change Remains Unlikely but Not Impossible – New Lines Institute, accessed June 19, 2025, https://newlinesinstitute.org/strategic-competition/regional-competition/real-time-analysis-iran-after-the-israeli-strikes-regime-change-remains-unlikely-but-not-impossible/

- Behind Tehran’s threats lies an economy on the brink – Ynetnews, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.ynetnews.com/business/article/rjljjeevlx

- Oil Exports, an Important Component of Iran’s Funding for Terrorism, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.terrorism-info.org.il/en/oil-exports-an-important-component-of-irans-funding-for-terrorism/

- FinCEN Advisory Highlights Iran Sanctions Evasion Red Flags | Insights – Holland & Knight, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.hklaw.com/en/insights/publications/2025/06/fincen-advisory-highlights-iran-sanctions-evasion-red-flags

- Sanctions and Impacts on Lasting Peace with Iran, accessed June 19, 2025, https://ucfglobalperspectives.org/blog/2025/01/03/sanctions-and-impacts-on-lasting-peace-with-iran/

- Explainer: The Iranian Armed Forces | Institute for the Study of War, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/explainer-iranian-armed-forces

- Iran Faces Its Toughest Test Since the War With Iraq – Expert Warns of Escalation Fallout, accessed June 19, 2025, https://caspianpost.com/interview/iran-faces-its-toughest-test-since-the-war-with-iraq-expert-warns-of-escalation-fallout

- Iran’s Civil Society Amid the Shadow of External Threats – Stimson Center, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.stimson.org/2025/irans-civil-society-amid-the-shadow-of-external-threats/

- How do Israelis and Iranians feel about the Israel-Iran war? – Northeastern Global News, accessed June 19, 2025, https://news.northeastern.edu/2025/06/17/israelis-iranians-the-israel-iran-war/

- Iran Update Special Report, June 18, 2025, Evening Edition | Institute for the Study of War, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-special-report-june-18-2025-evening-edition

- Urgent need to protect civilians amid unprecedented escalation in hostilities between Israel and Iran – Iran (Islamic Republic of) | ReliefWeb, accessed June 19, 2025, https://reliefweb.int/report/iran-islamic-republic/urgent-need-protect-civilians-amid-unprecedented-escalation-hostilities-between-israel-and-iran

- Trump says the US knows where Iran’s Khamenei is hiding and urges Iran’s unconditional surrender, accessed June 19, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/trump-iran-nuclear-israel-g7-132d92f3b5f4014cced1c5029d839ae9

- Israel isn’t close to victory over Iran | The Spectator, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/israel-isnt-close-to-victory-over-iran/

- Why America Must Join Israel Against Iran – Middle East Forum, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.meforum.org/mef-online/why-america-must-join-israel-against-iran

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed June 19, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asymmetric_warfare

- Examples of Asymmetric War Throughout History | UKEssays.com, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.ukessays.com/essays/history/historical-examples-of-asymmetric-war-history-essay.php

- Uncovering the Lessons of Vietnam – American Foreign Service Association, accessed June 19, 2025, https://afsa.org/uncovering-lessons-vietnam

- Lessons from the Vietnam War – Monthly Review, accessed June 19, 2025, https://monthlyreview.org/2016/12/01/lessons-from-the-vietnam-war/

- Asymmetric Conflict in Modern Warfare: Strategies, History, and Future Trends | Maya Reynolds – A Battle Within, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.abattlewithin.com/posts/asymmetric-conflict-44009

- 20 years on, what do you think the lesson of the Iraq & Afghan wars were? – Reddit, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/AskALiberal/comments/1j8fqgv/20_years_on_what_do_you_think_the_lesson_of_the/

- I wrote NATO’s lessons from Afghanistan. Now I wonder: What have we learned?, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/i-wrote-natos-lessons-from-afghanistan-now-i-wonder-what-have-we-learned/

- Lessons Learned: The Iraq Invasion | The Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/lessons-learned-iraq-invasion

- The enduring lessons of the Iraq War – History Guild, accessed June 19, 2025, https://historyguild.org/the-enduring-lessons-of-the-iraq-war/

- Israel Considering Regime Change in Iran as U.S. Weighs Its Options – The Soufan Center, accessed June 19, 2025, https://thesoufancenter.org/intelbrief-2025-june-18/

- U.S. Rapidly Reinforcing Military Strength In Middle East – AVweb, accessed June 19, 2025, https://avweb.com/aviation-news/u-s-rapidly-reinforcing-miltary-strength-in-middle-east/

- Trump’s Threat to Tehran and US Dilemma in Israel-Iran War – SpecialEurasia, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.specialeurasia.com/2025/06/17/trump-iran-israel-conflict/

- Middle East conflict threatens to exacerbate inflationary pressure on some things, accessed June 19, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/israel-iran-economy-trade-energy-inflation-1b7e5bef9c1414cb03cd14e40f4b19e5

- Stocks slump and oil prices jump as Trump urges Iran’s unconditional surrender, accessed June 19, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/stocks-markets-iran-tariffs-rates-b8cceca51655d69ee007b411bc9418b4

- What are the economic and market implications of the Israel-Iran conflict?, accessed June 19, 2025, https://am.jpmorgan.com/hk/en/asset-management/adv/insights/market-insights/market-updates/on-the-minds-of-investors/what-are-the-economic-and-market-implications-of-the-israel-iran-conflict/

- The Latest: Trump says all of Tehran should evacuate ‘immediately’, accessed June 19, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/israel-palestinians-iran-war-latest-06-16-2025-8633d291e79806ac498645ee04e059be

- Meeting in Wake of Israeli Air Strikes on Iran, Delegates in Security Council Urge De-escalation, Diplomacy to Prevent Further Strain in Conflict-Ridden Region, accessed June 19, 2025, https://press.un.org/en/2025/sc16087.doc.htm

- Iran: Emergency Meeting : What’s In Blue – Security Council Report, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/whatsinblue/2025/06/iran-emergency-meeting.php

- Russia’s strong ties with both Israel and Iran could help it emerge as a power broker, accessed June 19, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/russia-israel-iran-attack-mideast-nuclear-us-d5374c53a8b7188f29ffdc25486f5b55

- Russia, China Maintain Cautious Diplomacy Amid Israel-Iran Conflict, Despite Deepening Ties With Tehran – Algemeiner.com, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.algemeiner.com/2025/06/16/russia-china-maintain-cautious-diplomacy-amid-israel-iran-conflict-despite-deepening-ties-tehran/

- Developing | Xi urges Iran and ‘especially Israel’ to cease fire during call with Putin, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3315087/chinas-xi-jinping-and-russias-vladimir-putin-discuss-middle-east

- US Faces New Asymmetric Threats A Challenge to Military Supremacy – Army Recognition, accessed June 19, 2025, https://armyrecognition.com/focus-analysis-conflicts/army/analysis-defense-and-security-industry/us-faces-new-asymmetric-threats-a-challenge-to-military-supremacy

- Can the Israeli and Iranian economies sustain a war? – Al Jazeera, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/6/19/can-the-israeli-and-iranian-economies-sustain-a-war

- US troops, bases in Middle East could be targets in conflict with Iran – Military Times, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2025/06/18/us-troops-bases-in-middle-east-could-be-targets-in-conflict-with-iran/

- How the US has shifted military jets and ships in the Middle East, accessed June 19, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/us-military-middle-east-iran-israel-a4287f29c84b6eee954011ecd8a670d3

- Israel’s and Iran’s Military Adventurism Has Put the Middle East in an Alarmingly Dangerous Situation | Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed June 19, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/emissary/2025/06/israel-iran-war-regional-stability-military-adventurism-proxies?lang=en

MOST COMMENTED

Geopolitics / MENA Matters / Book Release / Current Affairs

La doctrine du chantage: Trump, Israël et la soumission des États arabes

GEW Intelligence Unit / Analyses & Commentaries / Research Paper

Iran’s Enduring Resilience: Why a Decisive Defeat is Elusive, Even with US Intervention

Littérature / France / Media / Nos livres / Podcast

Le cercle restreint (Roman) : Présentation+ Podcast critique

Iran / Gulf / Media / Israel / Essais / Podcast

La forteresse résiliente: Évaluer la puissance de l’Iran dans un contexte de confrontation moderne ( + critique en podcast)

Podcast / Iran / Collection: Geopolitics / Book Release / Current Affairs

The Resilient Fortress: Assessing Iran’s Power In A Modern Confrontation

Iran / Podcast / Briefings and Reports

La forteresse résiliente: L’Iran face à la confrontation moderne (Critique de livre en podcast)

Iran / Podcast / Briefings and Reports

La forteresse résiliente: L’Iran face à la confrontation moderne (Critique de livre en podcast)