Western Misrepresentations of Islam in the 20th Century

Hichem Karoui

Abstract:

This paper delves into the evolving Western perceptions of Islam throughout the tumultuous landscape of the twentieth century, intricately mapping the profound influence of political dynamics and cultural exchanges that have shaped these views. It scrutinizes the pervasive Orientalist frameworks that have long served to distill the complexities of Islamic cultures into simplistic, reductive stereotypes, often casting Islam and its adherents either as an impending threat or an exotic spectacle demanding intricate dissection.

Through meticulous and research-driven analysis, this investigation posits that such antiquated perspectives, steeped in historical narratives, not only lack accuracy but also credibility, failing to encapsulate the vibrant diversity inherent within both Muslim societies and Western contexts alike. The underlying argument contends that these misrepresentations profoundly undermine the multifaceted nature of cultural identity, leading to skewed public perceptions and policy implications.

The methodology proposed encompasses a critical dissection of media portrayals, scholarly discourses, and colonial narratives, each layer peeling back the persistent biases that shape societal understandings. This exploration beckons a more sophisticated engagement with Islam, revealing how distortions of representation can influence public sentiment and governmental policies. Importantly, it suggests that an authentic representation of Islamic traditions and the experiences of Muslims can catalyze empathy, paving the way for greater understanding and cooperation in pursuit of shared humanitarian objectives.

In doing so, this research aspires to transcend the superficialities of contemporary discourse surrounding Islam, inviting a deepened engagement with the intricate tapestry of cultural identities in our ever-more interconnected world. By fostering a nuanced appreciation of these complexities, the study champions a discourse that not only enriches understanding but also fortifies the bonds that unify diverse communities across the globe.

Keywords:

Islam and Orientalism, Western perceptions, media portrayal, colonial narratives, cultural representation.

Introduction:

Overview of Western perspectives on Islam in the 20th century

In the 20th century, Western perspectives on Islam were markedly influenced by political events, cultural exchanges, and scholarly discourse. The rise of nationalism in Muslim-majority countries reshaped the narrative around Islam as it became synonymous with anti-colonial movements. This led to a dual portrayal: one that emphasized Islamic fundamentalism as a threat and another that sought faux romanticism, often reducing diverse Muslim cultures to mere exotic caricatures. Such representations served to fuel both fear and fascination, creating a paradox where Islam was simultaneously vilified and idealized.

Moreover, media portrayals played a significant role in perpetuating stereotypes during pivotal moments like the Iranian Revolution and the Gulf Wars. The prevailing narratives often lacked nuance, depicting Muslims predominantly as either radical extremists or passive victims rather than agents of change within their societies. As intellectuals like Edward Said critiqued earlier Orientalist views, many in the West began to challenge these reductive images; however, they still struggled to present an authentic voice for Muslims themselves. This ongoing tension between understanding and misrepresentation reflects deeper biases embedded within Western thought—a complex interplay of power dynamics that calls for greater introspection in contemporary discourses surrounding Islam today.

1. Early Twentieth-Century Orientalism

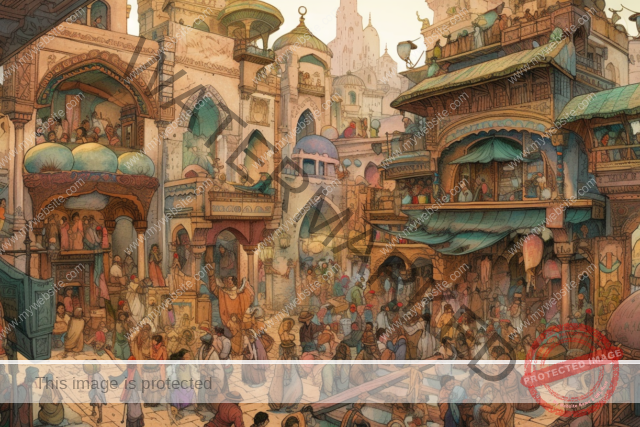

In the early twentieth century, Orientalism transcended mere aesthetic fascination; it evolved into a complex ideological construct that shaped Western perceptions of the East—particularly in relation to Islam.[1] This period marked a shift from romanticized depictions of exotic lands to an unsettling narrative steeped in power dynamics, where the East was often portrayed as irrational and barbaric, serving to justify colonial exploits.[2] Artists and writers like Lawrence of Arabia depicted the Arab world through a lens tinted by Western superiority, transforming diverse cultures into monolithic caricatures that catered to Western fantasies rather than authentic experiences.

This era also saw the increasing entanglement of literature with geopolitics. While some thinkers attempted to challenge existing stereotypes, major narratives remained fixated on tropes of mysticism and oppression, which painted Muslim societies as fundamentally antagonistic towards modernity.[3] Writers often cherry-picked elements of Islamic culture that aligned with their views while ignoring rich traditions that contradicted them.[4] Consequently, this selective representation not only distorted cultural realities but also entrenched harmful stereotypes that influenced public opinion and policy decisions for decades—a legacy still palpable today amid ongoing discourse surrounding Islamophobia and cultural misunderstanding.

– Influence of Edward Said’s work on understanding Orientalism

Edward Said’s groundbreaking work, *Orientalism*, reshaped the discourse surrounding Western representations of Eastern societies, particularly in their portrayal of Islam and its cultural facets. By framing Orientalism as a powerful construct through which the West defined itself against an idealized and often distorted image of the East, Said laid bare the underlying power dynamics at play. He deftly illustrated how literature, art, and academia were not merely reflective mediums but active participants in perpetuating stereotypes that served colonial ambitions.[5]

Yet, as we delve deeper into his influence, it becomes evident that Said’s insights extend beyond mere critique; they invite us to reevaluate contemporary narratives surrounding Islam and Muslim identities. His emphasis on representation prompts critical questions about who has the authority to speak for whom within cultural dialogues today.[6] This recognition empowers marginalized voices from Islamic cultures to reclaim their narratives—transforming them from passive subjects of Western scrutiny to active shapers of their own stories. In a world increasingly interconnected by media yet fractured by misunderstandings, revisiting Said’s ideas is more essential than ever for promoting cultural empathy and nuanced understanding in dialogue about religion and identity.

– Cultural and academic representations of Islam during this period

Cultural and academic representations of Islam during the 20th century were deeply influenced by a backdrop of geopolitical tensions and socio-political dynamics. While Western literature often portrayed Islamic societies through a lens of exoticism or fear, this oversimplified view neglected the rich diversity within Muslim communities. Scholars such as Edward Said critiqued these portrayals in Orientalism, yet even post-Said discourse frequently succumbed to binary thinking that pitted the ‘rational’ West against the ‘irrational’ East.[7] This dichotomy hindered genuine understanding and fostered stereotypes that linger in contemporary narrative.

In academia, there emerged an inclination to depersonalize Islamic cultures, framing them instead through theories rather than lived experiences. This resulted in an unsettling tendency to generalize vast traditions—such as Sufism, Sunni practices, and Shia beliefs—as monolithic phenomena rather than acknowledging their multifaceted realities.[8] As voices from within these cultures gained visibility—thinkers like Mohammed Arkoun, Hassan Hanafi, Abdolkarim Soroush and Fatema Mernissi—the discourse began to shift towards recognizing Islam’s dynamic interplay with modernity. Engaging deeply with both historical contexts and contemporary voices is essential for dismantling enduring myths while promoting a more nuanced understanding of Islam today—one that can bridge cultural divides rather than deepen them.

2. Colonial Narratives and Power Dynamics

Colonial narratives crafted by Western powers often served dual purposes: justifying imperial conquest and reshaping the identities of colonized societies. Within these narratives, Islam was frequently framed as a monolithic entity synonymous with despotism and backwardness.[9] This oversimplification not only distorted the rich diversity inherent in Islamic thought and culture but also served as a tool to legitimate colonial rule, positioning Western civilization as a supposed beacon of enlightenment.[10] By portraying Muslims as static and unchanging, colonizers stripped away the complexities of contemporary Islamic societies that were evolving alongside global socio-political shifts.

In examining these power dynamics, it becomes evident that colonial representations were not merely harmful stereotypes; they actively influenced policy decisions and international relations for decades. The creation of an us versus them dichotomy deepened mistrust between East and West, leaving scars that would manifest in geopolitical tensions long after independence movements swept through previously colonized nations.[11] Furthermore, by framing Muslim dissent against colonial rule as dark fanaticism rather than legitimate resistance for autonomy, colonial powers sought to undermine local agency while reinforcing their dominion over the narrative landscape [12]—a tactic still echoed in modern media portrayals today. Through this lens, the struggle against misrepresentation continues to resonate deeply within contemporary dialogues around identity and belonging among Muslims globally.

– Role of colonial powers in shaping perceptions of Islam

Colonial powers actively staged a narrative that painted Islam less as a religion and more as an ideology antithetical to Western values, using it to justify their imperial pursuits. The portrayal of Islamic societies through the lens of exoticism often served to reinforce stereotypes of barbarism and backwardness, breeding fear and misunderstanding among Western audiences. This distortion was particularly evident in literature, art,[13] and academic scholarship; works by colonial-era scholars frequently emphasized absurdities while neglecting the rich intellectual histories and cultural contributions within Islamic civilization—an act that ensured continued domination over these societies.[14]

In addition to outright misrepresentation, colonial regimes manipulated education systems in colonized regions to align local knowledge with Western ideologies.[15] By marginalizing traditional Islamic scholarship and promoting secular or Eurocentric frameworks, they effectively reshaped the educational landscape, leading new generations to adopt skewed perceptions of their own heritage. These distortions resonated throughout not only public sentiment but also policy decisions in the geopolitical sphere well into the 20th century—fostering a lingering trepidation around Islam that has persisted today.[16] Ultimately, this concerted effort by colonial powers constructed a monolithic view of a diverse faith while obscuring its multifaceted realities—resulting in misconceptions that continue to hinder meaningful dialogue across civilizations.

– Impact of colonial rule on Islamic societies and identities

Colonial rule had a profound and transformative impact on Islamic societies, reshaping identities in ways that continue to resonate today.[17] As Western powers imposed new political structures and economic systems, indigenous Islamic communities were often forced to negotiate their cultural traditions within these confines. This friction not only gave rise to nationalist movements but also spurred intellectual debates within Muslim circles about modernity and what it meant to be Islamic in an era of Western dominance.[18] Scholars like Ali Shariati or Muhammad Iqbal sought to reconcile traditional beliefs with modern ideals, challenging the notion that modernization necessitated a departure from Islam.

Moreover, colonial administrations frequently employed divide-and-rule tactics that separately marginalized various ethnic groups and sects within Islam—Sunni versus Shia, Arab versus non-Arab—ultimately distorting communal bonds.[19] The creation of artificial borders and categories altered established social networks, leading many Muslims to grapple with fragmented identities amidst a backdrop of colonial oppression.[20] In this crucible, we witness the genesis of hybrid identities—a merging of religious allegiance with secular patriotism—revealing how even under duress, communities sculpted new forms of identity reflective of both resilience and resistance against external control. Such complexities illustrate that the legacy of colonialism is not merely one of loss; it also entails an ongoing negotiation between tradition and innovation that shapes contemporary Islamic thought and practice across the globe.

3. Media Portrayals and Public Perception

Media portrayals of Islam have often straddled the line between sensationalism and simplification, contributing to a skewed public perception that shapes societal attitudes.[21] From the early 20th century, films and news coverage frequently depicted Muslims through a lens of mystery and danger, reinforcing stereotypes tied to violence or exoticism.[22] This reductionist view not only homogenizes a vast and diverse faith but also feeds into geopolitical narratives that justify conflict or intervention under the guise of “civilizing” missions.[23]

More recently, although some media outlets have made strides toward nuanced storytelling by featuring diverse Muslim voices and experiences, the legacy of past misrepresentation still lingers.[24] The prevalence of terms like terrorism juxtaposed with images from predominantly Muslim countries creates an automatic association in viewers’ minds that fosters misunderstanding rather than engagement. Furthermore, social media exacerbates this issue; viral content often prioritizes clicks over context, resulting in narratives that are not just misleading but harmful. As consumers of media, we bear responsibility for scrutinizing these portrayals critically while also advocating for stories that reflect the true complexity of Islamic cultures—stories filled with resilience, innovation, and community spirit that challenge existing stereotypes entrenched in the public consciousness.

– Analysis of key media narratives about Islam from the mid to late 20th century

Throughout the mid to late 20th century, key media narratives surrounding Islam were often entwined with geopolitical events and fueled by widespread cultural stereotypes. The portrayal of Muslims as either mystical idealists or fanatical extremists served to simplify a complex religion into digestible soundbites for Western audiences. In films and literature, Islamic culture was frequently exoticized,[25] presenting an ambiguous Other that both fascinated and instilled fear. This polarized representation could obscure the rich diversity within Muslim communities, reinforcing a monolithic view that belies the reality of varied beliefs and practices.

Moreover, during periods of heightened political tension—such as the Iranian Revolution in 1979 or the Gulf War in the early 1990s—the media often emphasized sensational narratives that painted Muslims through a lens of conflict.[26] Analyzing these portrayals reveals how power dynamics influenced public perception; images of angry mobs became synonymous with Islam itself while neglecting voices advocating for peace and reform within those societies.[27] Such representations perpetuated stereotypes and influenced social policy, deepening cultural divides at home while shaping international relations abroad. In challenging these entrenched narratives, we unearth opportunities for richer dialogues—one that acknowledges complexity over caricature.

– Effects of media representation on public opinion and policy-making

Media representation profoundly shapes public opinion, often acting as a powerful lens through which complex issues are simplified into digestible narratives. In the case of Islam, the Western media’s portrayal frequently intertwines elements of fear and misunderstanding, leaning towards stereotypes that paint the faith as monolithic and inherently opposing to Western values.[28] This not only distorts public perception but also frames Muslim communities within a context of suspicion and hostility, fostering an environment ripe for prejudice and discrimination.

Moreover, these skewed representations extend their influence into policy-making arenas, where politicians leverage public sentiment shaped by media narratives. For instance, policies surrounding immigration and national security often draw upon sensationalized depictions of ‘the other,’ leading to legislation that prioritizes security over human rights or cultural understanding.[29] As a result, the consequences manifest in systemic changes—ranging from targeted legislation to increased surveillance—reflecting an acceptance of misconceptions rather than informed discourse.[30] Addressing this misalignment is critical; it invites us to reconsider how we engage with diverse cultures within our societies while advocating for nuanced narratives that can foster empathy rather than division.

4. Political Contexts: Cold War Influences

The Cold War era served as a backdrop for the West’s complex relationship with Islam, intertwining geopolitical maneuvering with cultural misrepresentation. As the United States and the Soviet Union vied for global supremacy, both powers recognized Islam’s potential as a political force in regions like the Middle East, Africa and Asia. This realization prompted an intricate dance of support and suppression, where Western narratives often painted Islamic societies through outdated Orientalist lenses—viewing them primarily as ideological adversaries or fundamentalists rather than embracing their diverse cultures and histories.

Moreover, this political context amplified stereotypes that relegated Muslims to mere pawns within grand geopolitical strategies. The portrayal of Islamic movements was frequently steeped in fear-driven rhetoric, obscuring their genuine socio-political motivations and the societies’ aspirations for self-determination. As espionage activities unfolded discreetly amid overt military interventions, Western media leveraged these tensions to shape public opinion—a phenomenon evident in films and literature that demonized the “enemy” while glossing over shared human experiences. In doing so, these representations not only distorted perceptions of Islam but also risked perpetuating conflicts by fostering a disconnect between cultures that could have otherwise thrived through mutual understanding.

– US-Soviet rivalry’s role in framing the image of Islam

The US-Soviet rivalry during the Cold War played a significant role in framing the image of Islam, with both superpowers leveraging religious narratives to advance their geopolitical objectives. As tensions escalated, particularly following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Islam became increasingly associated with resistance and rebellion against oppression.

- **Media Portrayal:** The media in both the West and East began to depict Muslims largely through the lens of conflict. In Western narratives, Islamic fundamentalism was often linked to terrorism and extremism, feeding into a fear-based narrative that painted Muslims as threats to secular values and global stability.[31] Conversely, within Soviet propaganda, Islam was sometimes portrayed as a means for fostering solidarity among oppressed peoples against Western imperialism.[32]

- **Support for Extremist Groups:** The US response to Soviet actions included support for mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan—many of whom were motivated by Islamist ideologies—effectively romanticizing armed struggle framed through an Islamic perspective.[33] This not only strengthened certain fundamentalist interpretations but also established pro-Western Islamist leaders who could be used as bulwarks against perceived communist expansion.[34]

- **Cultural Exchange Dynamics:** The competition between these two powers affected cultural exchanges around Islam; while anti-communist sentiment frequently highlighted Muslim societies’ traditional values as superior alternatives to atheistic communism, it simultaneously reinforced negative stereotypes about militant factions within those societies.[35]

- **Post-Cold War Implications:** After the Cold War ended, lingering perceptions from this era continued shaping policy approaches towards predominantly Muslim nations or communities across regions such as the Middle East and Central Asia and Africa—fostering ongoing cycles where internal conflicts mingled with external interventions justified on grounds of combating “Islamic extremism.”

In summary, throughout decades marked by intense rivalry between two nuclear powers vying for ideological dominance globally—the collective portrayal emerged shaped significantly influenced by strategic interests that underscored dynamics surrounding identity politics with respect toward a diverse faith community such impacts persist even today amidst fluctuating international relations across continents.

– Geopolitical strategies involving Muslim-majority countries

In the labyrinthine landscape of modern geopolitics, Muslim-majority countries often find themselves at a critical crossroads between tradition and modernity, where their strategic importance is frequently undervalued or misrepresented in Western narratives. The geopolitical strategies of such nations are not merely responses to external pressures; they reflect deep-rooted historical legacies and cultural identities that shape their actions on the global stage. For instance, countries like Turkey and Indonesia have increasingly leveraged their unique positions within both regional dynamics and wider Islamic solidarity, positioning themselves as voices for moderate Islam while simultaneously managing relations with Western powers.

Moreover, developments in energy politics have only amplified the significance of Muslim-majority countries in the global arena. Nations like Saudi Arabia and Qatar wield substantial influence through their vast oil reserves, driving investments that extend beyond mere economic interests into political alliances that can reshape regional stability.[36] This interplay reveals a more complex reality: rather than being passive actors caught in Western conflicts, these nations actively craft their own narratives, engaging in diplomatic maneuvers that seek to balance sovereignty with collaboration against common threats—be it terrorism or climate change. Understanding these multifaceted strategies invites us to reconsider how we view these countries: not as mere chess pieces on a global board but as dynamic players with agency whose influences reach far beyond simplistic caricatures often portrayed in Orientalist discourse.

5. Academic Discourse and Institutional Biases

The academic discourse surrounding Islam in the 20th century has often maintained a dualistic narrative that not only misrepresents its rich tapestry but also reinforces institutional biases inherent within Western scholarship. Many scholars, shaped by their own cultural backgrounds and societal norms, have framed Islamic practices through a lens of skepticism rather than engagement. This has led to an academic environment where interpretations are frequently colored by preconceived notions, favoring sensational narratives over nuanced understandings. Such biases can marginalize authentic voices from within Muslim communities, reinforcing hegemonic views that diminish the complexity of diverse Islamic traditions.

Furthermore, institutional affiliations and funding sources play a critical role in shaping research agendas and outputs. Many academic departments prioritize studies that align with dominant geopolitical discourses or promote specific political interests, unintentionally sidelining perspectives that challenge prevailing stereotypes. This creates an echo chamber effect where alternative views find little traction, perpetuating misconceptions about Islam as monolithic or inherently conflictual. To dismantle these biases, there is an urgent need for interdisciplinary approaches that elevate indigenous scholarship and foster genuine cross-cultural dialogue—transforming academic inquiry into a more inclusive exploration of faith beyond mere ideological divides.

– Examination of scholarly works that contributed to biased views

Scholarly works throughout the 20th century have often served not merely as reflections of cultural understanding but as instruments that perpetuated biased views of Islam.[37] One notable phenomenon was the tendency among Western scholars to overly simplify and homogenize Islamic cultures, viewing them through a narrow lens centered on conflict and difference. Pivotal figures in the field may have aimed for rigorous analysis, yet their frameworks frequently reinforced stereotypes, framing Muslims as either exotic subjects or agents of violence.[38] This duality contributed to what Edward Said termed “Orientalism,” where anthropological studies became vehicles for colonial narratives rather than embracing the rich diversity present within Islamic traditions.[39]

Moreover, these scholarly contributions were often sanctioned by institutional biases that favored sensationalism over nuanced dialogue. Research funding tended to align with political agendas,[40] inadvertently promoting works that dramatized discord while sidelining those highlighting coexistence and cooperation between cultures. For instance, texts focused predominantly on jihadist interpretations of Islam gained traction at academic forums and publishing houses alike, overshadowing burgeoning research on peaceful Islamic teachings or interfaith efforts across communities.[41] By examining how such biases shaped understandings of Islam in Western discourse, we uncover not just a distortion of reality but an ongoing responsibility for contemporary scholars to pursue more balanced representations—recognizing multiplicities rather than settling for monolithic portrayals rooted in outdated perceptions. [42]

– Institutions that perpetuated stereotypes through research and publications

Throughout the 20th century, several institutions—both academic and governmental—played critical roles in perpetuating stereotypes about Islam through their research and publications. Prominent universities often prioritized inquiries that reinforced existing biases rather than fostering nuanced understanding.[43] Scholars affiliated with these institutions frequently approached Islamic studies from a colonial lens, portraying Muslim societies as stagnant or inherently violent, thus painting a skewed narrative that aligned with Western imperial objectives.[44] This not only affected the academic discourse but also shaped public perceptions, creating an enduring cultural dichotomy between the ‘civilized’ West and the ‘backward’ East.[45]

Moreover, think tanks and policy institutes began producing reports that generalized complex socio-political dynamics into binary narratives of good versus evil. These oversimplifications perpetuated fear-based imagery in media portrayals, leading to widespread misconceptions about Islamic beliefs and practices.[46] As such institutions bore the weight of authority in shaping public opinion, they inadvertently contributed to an environment ripe for discrimination and xenophobia, framing Muslims as ‘the other’ while sidelining vast swathes of rich history and diversity within the Islamic world.[47] Challenging these entrenched stereotypes requires not only reevaluating historical academic work but also amplifying voices from within Muslim communities that illuminate their multifaceted identities beyond Western narratives.

6. Literature and Film: Artistic Depictions

Literature and film have long served as potent mediums through which Western perceptions of Islam are filtered and distorted. These artistic depictions often prioritize sensationalism over authenticity, framing Islamic cultures within a narrow lens of exoticism or threat.[48] For example:

- Hollywood films have a long history of perpetuating negative stereotypes about Muslims and Arabs,[49] depicting them as terrorists, fanatics, or backward/uncivilized people.[50] This trend extends from early films like “The Sheik” (1922) to modern blockbusters.

- Common stereotypes in Western media include portraying Muslim men as violent predators and Muslim women as oppressed victims in need of Western liberation.[51] These depictions ignore the diversity and complexity of Muslim societies.

- There is a tendency to homogenize and conflate different Middle Eastern, Arab, and Muslim identities in Western portrayals.[52] For example, using Moroccan actors to play Lebanese characters or mixing up different Arabic dialects.

- The events of 9/11 amplified existing stereotypes, leading to a surge in portrayals of Muslims as potential threats or terrorists in post-9/11 Hollywood films.[53]

- Even some contemporary novels by Muslim authors living in the West have been criticized for unwittingly perpetuating neo-Orientalist images by focusing heavily on issues like honor killings and patriarchal violence.[54]

- Edward Said’s influential work “Orientalism” analyzed how Western scholars and artists have historically constructed an exotic, oversimplified view of “the Orient” that serves imperialist agendas.[55]

- Media depictions often juxtapose Islamic religious practices with scenes of violence, implying an intrinsic link between Islam and terrorism.[56]

- There is a lack of nuanced, multi-dimensional Muslim characters in mainstream Western media. When Muslims are portrayed, it is often in stereotypical roles.[57]

These patterns in literature and film have contributed to shaping Western perceptions of Islam in ways that emphasize otherness, exoticism, and threat rather than providing authentic, diverse representations of Muslim cultures and individuals. While there have been some efforts to challenge these stereotypes in recent years, the overall trend in Western media has been to prioritize sensationalism over accuracy when depicting Islam and Muslims.

7. Consequences for Muslim Communities

The misrepresentations of Islam in Western discourse have had profound and lasting consequences for Muslim communities around the globe. One of the stark realities that emerged from these distortions is the internalization of negative stereotypes, leading many Muslims to grapple with a fractured identity. In societies where they are often portrayed as monolithic, individuals find themselves navigating a landscape rife with discrimination and societal suspicion, which can stifle their ability to express both their faith and their culture freely.

Moreover, the sensationalism surrounding Islam has catalyzed an increase in hate crimes and xenophobia against Muslims. The rise of far-right movements leveraging these misconceptions fosters environments where narratives rooted in fear overshadow those grounded in understanding. This phenomenon restricts dialogue between communities and perpetuates cycles of distrust that hinder social cohesion. Ultimately, these consequences reflect not only on individual lives but also on the broader tapestry of multicultural societies striving for mutual respect and peace in an increasingly polarized world.

– Socio-political ramifications for Muslims living in Western societies

The socio-political ramifications for Muslims living in Western societies are multifaceted and deeply intertwined with historical narratives and modern geopolitical dynamics. The rising tide of Islamophobia, often fueled by sensationalized media portrayals, has not only marginalized Muslim voices but has also resulted in tangible discrimination.[58] Policies that disproportionately target Muslim communities—be it through surveillance programs or travel bans—reflect a broader systemic bias undergirded by misunderstandings about Islam itself.[59] This environment fosters social alienation, as many Muslims feel they must navigate a fine line between cultural preservation and the pressure to assimilate within an often hostile societal framework.[60]

Furthermore, the misrepresentation of Islam as monolithic neglects the rich tapestry of beliefs and practices among Muslims across different cultures. This is particularly salient in discussions around representation in politics: when Western narratives default to stereotypes, it becomes challenging for Muslim politicians to advocate effectively on behalf of their communities.[61] Consequently, many potential leaders from these backgrounds may face uphill battles in gaining public trust or office, perpetuating a cycle where diverse perspectives are sorely missed in policy-making processes that directly affect them. By recognizing the complexities within Islamic identities—and advocating for genuine representation—we can dismantle harmful stereotypes and usher in more inclusive dialogues that reflect the realities of contemporary Muslim experiences beyond mere caricatures rooted in fear or misunderstanding.

– Legal and social challenges faced by Muslim minorities

Muslim minorities frequently navigate a landscape fraught with legal and social challenges, intricately woven into the fabric of their lived experiences. In many Western countries, the perpetuation of stereotypes about Islam often leads to discriminatory legislation that disproportionately affects these communities.[62] For instance, anti-terrorism laws designed to protect national security can inadvertently target innocent individuals, stifling their rights and freedoms under the guise of public safety. The chilling effect extends beyond legal repercussions; it fosters an environment where Muslims may feel compelled to alter their identities or practices to avoid scrutiny.[63]

Socially, Muslim minorities contend with a persistent othering that transforms them into perpetual outsiders in societies they call home. This marginalization is exacerbated by underrepresentation in media narratives and political discussions, which tend to overshadow their contributions and multifaceted identities.[64] The result is an erosion of trust between communities and institutions—further entrenching isolation rather than integration. By recognizing these nuanced challenges not as anomalies but as systemic issues embedded within broader societal frameworks, we can begin advocating for inclusive policies that respect and honor diverse identities while dismantling harmful stereotypes perpetuated throughout the 20th century and beyond.[65]

Conclusion

In conclusion, the misrepresentations of Islam in the 20th century reveal not just a distortion of a faith and its followers but also an underlying anxiety within Western societies about their own identities. The narratives crafted through literature, film, and politics not only marginalized Muslim voices but also reflected deeper socio-political conflicts. These portrayals often served as mirrors reflecting Western fears and prejudices rather than the realities of Islamic belief systems and cultural practices.

By critically examining these misconceptions, we not only challenge historical stereotypes but also pave the way for a more nuanced understanding that transcends binary depictions of us versus them. In recognizing the richness and diversity within Islamic traditions, we invite an enriching dialogue that can foster empathy over animosity. Thus, dismantling these outdated paradigms is essential—not solely for justice to those represented but for promoting a global discourse grounded in respect and accurate representation. Ultimately, this journey towards understanding invites us to reflect on our shared humanity and challenges us to rewrite narratives that embrace complexity rather than simplify it.

– Need for more balanced, nuanced understandings moving forward

A more balanced, nuanced understanding of Islam is crucial as we navigate the complexities of a global society increasingly defined by diversity and interconnectedness. The binary perceptions that often dominate discourse—casting the East as the exotic ‘Other’ and the West as rational—fail to capture the rich tapestry of beliefs, practices, and experiences within Muslim communities. It is essential to recognize that Islam is not a monolith; interpretations and expressions vary widely across regions, cultures, and individual narratives. This recognition invites us to unravel existing biases while fostering dialogues that emphasize common humanity rather than stark differences.

Moreover, engaging with scholars from diverse backgrounds can illuminate underrepresented voices within Islamic discourse. Emphasizing local perspectives allows us to challenge Western-centric frameworks that have too often dictated conversations about faith in a global context. Acknowledging historical injustices in representation helps dismantle stereotypes perpetuated through media portrayals or academic scholarship rife with Orientalist undertones. By prioritizing inclusivity and complexity in discussions around Islam, we take significant strides toward mutual respect and understanding—paving the way for collaborative futures built on empathy rather than fear.

– Call for inclusive histories that recognize diverse experiences within Islam

In the quest for a more inclusive narrative about Islam, it is essential to spotlight the myriad experiences that have shaped Muslim identities across cultures and centuries. Often overshadowed by dominant discourses, these diverse histories offer rich perspectives that challenge monolithic portrayals of Islam. By embracing voices from within various communities—whether through literature, oral traditions, or historical scholarship—we can dismantle stereotypes and foster a deeper understanding of Islamic practices as they intersect with local customs, gender roles, and socio-political contexts.

Moreover, recognizing the contributions of marginalized groups—women in different societal roles, ethnic minorities within Muslim-majority regions, and ex-Muslim perspectives—can help counteract reductive narratives that fixate on conflict or extremism. This approach not only enriches our comprehension of Islamic civilization but also reveals how resilience and innovation thrive intertwined with faith. As we strive for authenticity in representation, let us commit to exploring stories that accentuate diversity over orthodoxy; doing so will illuminate the multifaceted realities of Muslims around the globe and open pathways for dialogue rooted in respect rather than fear.

Notes and References

[1] W. F. Albright. “Islam and the Religions of the Ancient Orient.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, 60 (1940): 283. https://doi.org/10.2307/594418.

[2] E. W. Capen. “Sociological Appraisal of Western Influence in the Orient.” American Journal of Sociology, 16 (1911): 734 – 760. https://doi.org/10.1086/211925.

[3] W. F. Albright. (1940)

[4] A. Mingana. “A Semi-official Defence of Islam.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 52 (1920): 481 – 488. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0035869X00148531.

[5] Edward Said. Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient, Penguin.1995.

[6] See : Asif Bayat. “Islam and Democracy: What is the real question?” Nhwad Center for Studies and Research. April 19, 2020. https://bit.ly/4cyMM5V

[7] David Zarnett. “Defending the West: A Critique of Edward Said’s Orientalism.” (2008). https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.45-5134.

Sajida Abed Kadhim. “Criticism of the discourse and Oriental thought according to Muhammad Abed Al-Jabri A Critical Analytical Study of Vision and Approach.” Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy, 11 (2020): 2096-2106. https://doi.org/10.31838/SRP.2020.12.321.

[8] Jawad Syed and Edwina Pio. “Unsophisticated and naive? Fragmenting monolithic understandings of Islam.” Journal of Management & Organization, 24 (2018): 599 – 611. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2018.55.

See also: A. Ibrahim. “Contemporary Islamic thought: a critical perspective.” Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations, 23 (2012): 279 – 294. https://doi.org/10.1080/09596410.2012.676781.

[9] F. Dallmayr. “Orientalism and Islam: European Thinkers on Oriental Despotism in the Middle East and India . By Michael Curtis. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009. Perspectives on Politics, 8 (2010): 654 – 656. https://doi.org/10.1017/S153759271000071X.

[10] Mona L. Russell. “A Different Shade of Colonialism: Egypt, Great Britain, and the Mastery of the Sudan.” African Studies Review, 47 (2004): 230. https://doi.org/10.2307/3559390.

[11] Jesse Benjamin. “Restoring the Culture of Peace in Islamic East and Northeast Africa.” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 4 (2009): 85 – 91. https://doi.org/10.1080/15423166.2009.495274919471.

[12] F. Burgat. “Face to Face With Political Islam.” I. B. Tauris (2003).

[13] Al-Dagamseh, Abdullah M; and Golubeva, Olga. “Khaled Hosseini’s A Thousand Splendid Suns as a Child-Rescue and Neo-Orientalist Narrative.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 19.4 (2017): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.3057>

[14] Momin, A. R. (1989). Islamization of Anthropological Knowledge. American Journal of Islam and Society, 6(1), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.35632/ajis.v6i1.2697

[15] Bryant, K. “Education as Politics: Colonial Schooling and Political Debate in Senegal, 1850s-1914,” 2015.

[16] Hopner, Veronica, Darrin Hodgetts, Nick Nelson, and John Battersby. “Islam in the News: Persistent yet Changing Characterisations”, Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 11, 3 (2023): 287-310, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/21659214-bja10064

[17] Imperial Identities: Stereotyping, Prejudice and Race in Colonial Algeria Patricia M. E. Lorcin. Review by: William B. Cohen.The American Historical Review. Vol. 101, No. 5 (Dec., 1996), p. 1594.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2170289

[18] “أن تكون مسلماً في مجتمع غير مسلم: الحوار والتفاهم في ظل التنوع الثقافي”. فريق العلوم الاجتماعية (صوت المتوسط).إشراف : د. هشام القروي. منشورات عالم الشرق والغرب. لندن ، 2024.

[19] Rajit K. Mazumder. “Muslim Minority Against Islamic Nation: The Shias of British India and the Demand for Pakistan, 1940–45.” Studies in History, 38 (2022): 133 – 161. https://doi.org/10.1177/02576430221120312.

[20] Subhasis Ray. “Beyond Divide and Rule: Explaining the Link between British Colonialism and Ethnic Violence.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 24 (2018): 367 – 388. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2018.1522745.

[21] Hopner, et al., (2023). Op. Cit.

[22] Riggs, Kristy. Review of Representations of the Orient in Western Music: Violence and Sensuality. Notes 68, no. 3 (2012): 596-599. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/not.2012.0034.

[23] Rubina Ramji. “Examining the Critical Role American Popular Film Continues to Play in Maintaining the Muslim Terrorist Image, Post 9/11.” Journal of Religion and Film, 20 (2016): 4.

[24] Zempi, I., Chakraborti, N. (2014). Constructions of Islam, Gender and the Veil. In: Islamophobia, Victimisation and the Veil. Palgrave Hate Studies. Palgrave Pivot, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137356154_2

[25] Sadiya Abubakar, Md. Salleh Yaapar and S. H. Muhammad. “(Un)reading Orientalism in Sherry Jones’ The Jewel of Medina.” GEMA Online Journal of Language Studies, 19 (2019): 169-183. https://doi.org/10.17576/gema-2019-1904-09.

[26] Lanouar Ben Hafsa. “Overcoming the “Other’s” Stigma: Arab and Muslim Representations in US Media and Academia.” International Journal of Social Science Studies (2019). https://doi.org/10.11114/IJSSS.V7I5.4446.

[27] Edward Said, Covering Islam. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1981.

[28] F. Poorebrahim and G. Zarei. “How is Islam Portrayed in Western Media? A Critical Discourse Analysis Perspective.” International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 1 (2013): 57-75.

[29] Tariq Amin-Khan. “New Orientalism, Securitisation and the Western Media’s Incendiary Racism.” Third World Quarterly, 33 (2012): 1595 – 1610. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2012.720831.

[30] Hichem Karoui. Breaking the Veil: Unmasking Stigma Against Islam in the West. Global East-West. London. (2024).

[31] E. Said. (1981). Op. Cit.

[32] A. Bennigsen, P. Henze, G. K. Tanham and S. E. Wimbush. “Soviet Strategy and Islam.” (1991). https://doi.org/10.2307/2500628.

[33] O. Roy. “Islam in the afghan resistance.” Religion in Communist Lands, 12 (1984): 55-68. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637498408431111.

[34] Eden Naby. “The concept of jihad in opposition to communist rule: Turkestan and Afghanistan.” Studies in Comparative Communism, 19 (1986): 287-300. https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-3592(86)90026-8.

[35] Citino, N. J. (2012). “The Ottoman Legacy in Cold War Modernization.” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 44(2), 301-323.

Khalid, A. (2007). “The Soviet Union as an Imperial Formation: A View from Central Asia.” In A. L. Stoler, C. McGranahan, & P. C. Perdue (Eds.), Imperial Formations (pp. 113-139). School for Advanced Research Press.

[36] A. Jaffe and Jareer Elass. “War and the Oil Price Cycle.” Journal of International Affairs, 69 (2015): 121. See also:

Ghoble, Vrushal T. 2019. “Saudi Arabia–Iran Contention and the Role of Foreign Actors.” Strategic Analysis 43 (1): 42–53. doi:10.1080/09700161.2019.1573772.

[37] F. Dallmayr. “Orientalism and Islam: European Thinkers on Oriental Despotism in the Middle East and India . By Michael Curtis. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.” Perspectives on Politics, 8 (2010): 654 – 656.

[38] Atmaja, D. S. “The So-Called ‘Islamic Terrorism’: A Tale of the Ambiguous Terminology.” Al-Albab 5 (2016): 105–22.

[39] G. Maltese. “Islam Is Not a “Religion” – Global Religious History and Early Twentieth-Century Debates in British Malaya.” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion (2021). https://doi.org/10.1163/15700682-12341521.

[40] Z. Kazmi. “Radical Islam in the Western Academy.” Review of International Studies, 48 (2021): 725 – 747. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210521000553.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Přemysl Rosůlek. “Editorial: Reflections on Islamophobia in Central and Eastern Europe.” Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics, 12 (2018): 151 – 161. https://doi.org/10.2478/jnmlp-2018-0011.

[43] Dallmayr, F. (2010), op. Cit.

[44] A. Jafari. “The role of institutions in non-Western contexts in reinforcing West-centric knowledge hierarchies: Towards more self-reflexivity in marketing and consumer research.” Marketing Theory, 22 (2022): 211 – 227. https://doi.org/10.1177/14705931221075371.

[45] Přemysl Rosůlek. “Editorial: Reflections on Islamophobia in Central and Eastern Europe.” Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics, 12 (2018): 151 – 161. https://doi.org/10.2478/jnmlp-2018-0011.

[46] Leon Moosavi. “Orientalism at home: Islamophobia in the representations of Islam and Muslims by the New Labour Government.” Ethnicities, 15 (2015): 652 – 674. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796814525379.

[47] J. Schwedler. “Studying Political Islam.” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 43 (2011): 135 – 137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743810001248.

[48] Sutkutė, Rūta. 2020. “REPRESENTATION OF ISLAM AND MUSLIMS IN WESTERN FILMS: AN ‘IMAGINARY’ MUSLIM COMMUNITY”. EUREKA: Social and Humanities, no. 4 (August), 25-40. https://doi.org/10.21303/2504-5571.2020.001380.

[49] Eijaz, A. (2018). Trends and Patterns of Muslims’ Depictions in Western Films. An Analysis of Literature Review. Mediaciones, 14(21), 19-40. doi: 10.26620/uniminuto.mediaciones.14.21.2018.19-40

[50] Shaikh Ansari, Hiba . “The Misrepresentation of Muslims in Film: Examining Biased Portrayals and Their Impact.” TJR, August 16, 2023. https://www.thejamiareview.com/the-misrepresentation-of-muslims-in-film-examining-biased-portrayals-and-their-impact/

[51] Ibid. See also: Kitchlew, Iffah Abid. “Hollywood’s Relentless Discriminatory Depictions of Arab Characters.” The Daily Q, 2020. https://thedailyq.org/10468/magazine/hollywoods-relentlessly-discriminatory-depictions-of-arab-characters/.

Eijaz, A. (2018), op. Cit.

[52] Sutkutė, R. (2020), op. Cit.

[53] Qamar, Ayesha, Sadaf Irtaza, and Syed Yousaf Raza. 2024. “Islamophobia in Hollywood Movies: Comparative Analysis of Pre and Post-9/11 Movies”. Journal of Development and Social Sciences 5 (1). Gujranwala, Pakistan:529-37. https://doi.org/10.47205/jdss.2024(5-I)48. Also, see: Dellacasa, Claudia, and Hannah McIntyre. “Introduction: Reframing Exoticism in European Literature.” MHRA Working Papers in the Humanities 14 (December 9, 2019): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.59860/wph.a6b239d.

[54] Wahid, Muhammad Abdul. 2023. “From Orientalism to Neo-Orientalism: Medial Representations of Islam and the Muslim World.” Textual Practice, December, 1–20. doi:10.1080/0950236X.2023.2288112.

[55] Said, E., op. Cit.

[56] Eijaz, A. (2018), op.Cit.

[57] Sutkutė, R. (2020), Op. Cit. Kitchlew, Iffah Abid.(2020), op.Cit.

[58] S. Murshed and S. Pavan. “Identity and Islamic Radicalization in Western Europe.” Civil Wars, 13 (2009): 259 – 279. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698249.2011.600000.

[59] A. Messina. “Muslims and the State in Britain, France, and Germany.” Perspectives on Politics, 4 (2006): 209 – 210. https://doi.org/10.1017/S153759270667014X.

[60] Abdulkader Sinno. “The Politics of Western Muslims.” Review of Middle East Studies, 46 (2012): 216 – 231. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2151348100003438.

[61] Tasawar Baig and Saadia Beg. “Islam and the West: The Politics of Phobia.” (2018). https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350986336.ch-007.

[62] Zeynep Sezgin. “Islam and Muslim Minorities in Austria: Historical Context and Current Challenges of Integration.” Journal of International Migration and Integration, 20 (2018): 869-886. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12134-018-0636-3.

[63] Asif Mohiuddin. “Muslims in Europe: Citizenship, Multiculturalism and Integration.” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 37 (2017): 393 – 412. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602004.2017.1405512.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Zoila Combalía. “New Social and Legal Challenges Resulting from the Presence of Islam in 21st Century European Societies.” International and Comparative Law Review, 20 (2020): 113 – 128. https://doi.org/10.2478/iclr-2020-0020.

MOST COMMENTED

Book Release / Podcast / Fiction / Literature / Media

Isabelle Richard’s Novel, “The Unwritten Chapter” + Podcast Review

Literature / Media / Book Release / Podcast / Fiction

The Inner Circle : A Political Fiction by Hamon de Quillan + PODCAST REVIEW

Current Affairs / New Release / International Affairs / Iran / Podcast / Gulf / Geopolitics / Our Books / MENA Matters / Islam / Media / Israel / Middle East

The Blackmail Doctrine: Trump, Israel, And The Arab Compliance + PODCAST REVIEW

Book Release / Current Affairs / Geopolitics / MENA Matters

La doctrine du chantage: Trump, Israël et la soumission des États arabes

France / Media / Nos livres / Podcast / Littérature

Le cercle restreint (Roman) : Présentation+ Podcast critique